BEST 15 LOOKS FROM THE RESET SHOW 2025 AT CENTRAL SAINT MARTINS

September in fashion is a time where brands present their novelties for next season and magazines publish the latest trends that are going to carry the fall-winter of each year; in the case of December there are two main ideas: gifting campaigns and the RESET Show of Central Saint Martins. A show that “repositions clothing as critical artefacts that reflect complex cultural identities” as Stephanie Cooper, Pathway Leader BA Fashion Design: Communication, said over her stories via Instagram after the show ended.

Relevant points of view are expressed over 154 looks that intertwined ideas from all over the world with sustainable white fabric in a three week project, that served as the perfect platform to launch yourself to the fashion industry. Creating desire for your ideas and your way of understanding fashion. There is also the collaboration with the first year BA Fashion Communication: Image and Promotion students, who are responsible for all the promotional content and production of the show.

This year the whole idea was to represent the performative aspect of a domestic setting, called The HOUSE. A white key that allows us to understand the safety aspect that allows us to create control at our houses, from the dining room to the bedroom we can observe up-close the out-of-the-box garments created to rethink what each student can bring to the table. Let’s sit down and understand our 15 favorite proposals out of the whole show.

Ethan Simpkins (@ethansimpkinss)

Alvaro Ramos: What was the starting point for this look?

Ethan Simpkins: For me Lost is a feeling of complete helplessness, for when you feel the path beneath you that you’ve been trying to walk for so long falls away and then there is nothing but, then that’s where you must stop and become the way. While it may last for only a brief moment it feels like everything, the only thing you can feel which can be so isolating but so extraordinary to overcome.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

ES: I would say the aspect that sits most importantly within contemporary fashion is the fact that I wanted to reflect how I had felt without any need to hide it through something chic or attractive and while there are many people that do this. I feel that within the larger spaces in fashion there is always a motivation for that expression to be attractive or understandable at face value but to me, the fact that I am given a platform just to express how I feel is the most important part of this.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look, and what would you push further if you had more time?

ES: The strongest aspect for me is something that can’t necessarily be translated through images, which is unfortunate but I will try my best to describe it. The material feel of the garments was my favourite part. The hardened table linen that sat still within curved interlaced shapes almost like a porcelain vase. The tall standing line’s, created with paper, remained unwavering even when thwy could have been snapped by even a little force. To me they reflect the vulnerability of sharing these emotions and feelings, to stand tall is hard especially when you could shatter in an instant like the paper. Looking back I wish I could have spent more time building these things up more and around the body. Alongside my draping which I wish I could have done better but hopefully my next project will build on those things.

Jago Solloway (@jago.solloway)

AR: What was the starting point for this look? How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

JS: The modern samurai: jacket hand cut and full outfit sewn by me. For my reset project, I looked into the word “displaced” from which I then explored the power of tattoos and how this displaces the yakuza from Japanese society. I took this further and delved deeper into the yakuza mentality, from which they say “we are the modern samurai”. I found this contrast of the beauty of the tattoos paired with the actions of the yakuza truly fascinating and so created these pieces in response.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look, and what would you push further if you had more time?

JS: I’d say this lies in the cooperation of the various techniques used coming together – with the lacing to the pleating to the cutting out, it all fits together. If I had more time I would’ve loved to have made a stronger look for the shoe – taken time to learn how to make it look more professional.

Lucas Mathison (@lucas.mathison)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

LM: With Reset’s theme this year being The House, I took inspiration from the process of sifting through the ashes of my childhood home, which was lost earlier this year in the Los Angeles Eaton fire. Over the summer, I put together a book of photographs I’d taken during the sifting process. For Reset, I used this book as my sketchbook, with these images acting as my sole source of inspiration.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

LM: The process of creating my look was extremely personal, and honestly cathartic, so I wasn’t consciously thinking about the outcome in relation to any contemporary fashion discourse beyond my own experience. That said, Reset as a whole encourages students to consider what messages they want to stand behind, whether personal or universal. Because of the visibility and publicity surrounding the show, it creates a unique opportunity to challenge existing systems, and I think many people took advantage of that this year.

Two protests took place during Reset. One led by PDP in response to the potential loss of the Platform Theatre, and another protesting L’Oréal’s sponsorship of CSM in solidarity with Palestine. While the intentions behind my own Reset process and outcome were more personal, I stand behind both protests and am proud to have been indirectly involved in a show that allowed space for them to happen.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look, and what would you push further if you had more time?

LM: In my opinion, the strongest element of my look is also the element I would have liked to push further. I had the Ultrasuede we were given laser cut to resemble the exposed metal mesh that once held the walls of my home together, then boned it to create the draped piece seen on the right side of the garment.

I was happy with the outcome of the laser cutting, especially how stretching the fabric over the boning highlighted the pattern. However I don’t feel I was able to give the material the justice it deserved, as the piece kind of functioned more as a sculpture on the body than an actualized garment.

With more time, I would have liked to develop this piece into a sort of overcoat or cape. The narrative supporting the look was centred around the idea of a ghost trapped in the act of sifting through the ashes of my home, and I imagined this element functioning as a cape, similar to what the Phantom wears in The Phantom of the Opera.

Maggie Deng (@maggiedeng.007)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

MD: I have always been inspired by my friend and model, Elliott, for his music, sculptural work, and spontaneity. The RESET project allowed me to explore this influence, to investigate and engage with him as an artist. Our conversations shaped my ideas, and his choice of materials informed my early process. In many ways, he became the starting point of this project.

Throughout my development, I have drawn on my past collaboration with Elliott, from deconstructed workwear trousers into a crossbody bag to a balaclava covered in hi-vis reflective fabric. This project was another chapter in our ongoing exploration as individual artists, constantly inspiring each other. I wanted the garment to reflect our shared journey, to mark this moment in time. The hi-vis fabric responded dynamically to the runway environment, under flashing cameras and varied lighting, the garments transformed, creating shifting reflections and glows that added depth and movement. To me, the Reset look was a physical reflection of the personal dialogue and influence between 2 artists.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

MD: The volume in the garment is created through the cutting of strips, which are curled and knotted into one another to create space and structure. I was particularly interested in achieving volume while producing little to no waste, I was interested in an approach that challenged traditional methods of construction and encouraged a more considered use of fabric.

The trousers are carefully measured and fitted to the model to ensure ease of movement and confidence while walking. The coat is designed to be worn in multiple variations, as explored through my sketchbook development, allowing the wearer to interact with and reinterpret the piece.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

MD: Looking ahead, I aim to further develop this project across other mediums while continuing to refine the look into a new, wearable piece.

Riley Steifman (@rileysteifman)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

RS: This look is the fusion of myth, folklore, and winter ritual. Inspired by ancient legends from Bulgaria, the Austrian Alps, Norway, and Iceland, I drew from haunting Christmas monsters such as the Kukeri, Krampus, Perchten, Fossegrimen, and Draugr. By merging their influences into a new narrative of my own, I created an entirely original character, presented here today.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

RS: The look positions itself within contemporary fashion discourse by challenging conventional wearability, proposing an expressive, emotionally driven celebration of maximal creativity, reclaiming myth, fear, and the grotesque as alternative forms of beauty and empowerment. I aimed to capture a performative, multi-sensory experience, where the body becomes both sculpture and performer, an experience shaped by story, sound, and the moving body.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

RS: I feel the headpiece represents the strongest element of this look. Its creation was a physical process, the more it is engaged with and explored, the more it transforms and grows.

Seungjoon Park (@s_jooon1122)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

SP: The starting point for this look was the idea that change does not begin with a visible shift in form, but at the moment we step away from the familiar forces of inertia and gravity that shape our behavior and perception. Humans tend to remain in states that feel stable and safe, both physically and psychologically, and I was interested in the moment when that stability begins to loosen — just before one state turns into another.

To explore this idea, I used flying artefacts as a central reference. Objects such as kites, paragliders, parachutes, balloons, airplanes, rockets, and spacecraft represent humanity’s gradual attempt to move away from gravity. These artefacts are not only technical achievements, but records of human intention, each marking a step away from inertia. This look focuses on that initial shift — when balance starts to change and transformation appears not as a finished result, but as an ongoing process.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

SP: This work does not aim to directly engage with or critique contemporary fashion discourse. It began from a personal question rather than from trends or theoretical frameworks within fashion. My focus was not on responding to the fashion system itself, but on using clothing as a way to explore a moment of change — specifically, the transition from a stable state into something unknown. In that sense, the garments function less as style statements and more as structures that hold movement and transition. Rather than offering a clear critique, the work suggests an alternative approach: treating fashion not as a finished outcome, but as something that exists during a process of change.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

SP: This show required students to produce their work using only a single color. Because of this limitation, many pieces became one-off statements focused on expressing identity within the context of the show. Instead of following that approach, I focused on the garment as something that functions as a whole. The strongest element of this look is the attention to small movements and subtle changes, and how they are translated into construction. Each piece was designed to work together rather than exist as an isolated statement. With more time, I would further refine how these movements are developed across multiple garments, strengthening the continuity between each piece.

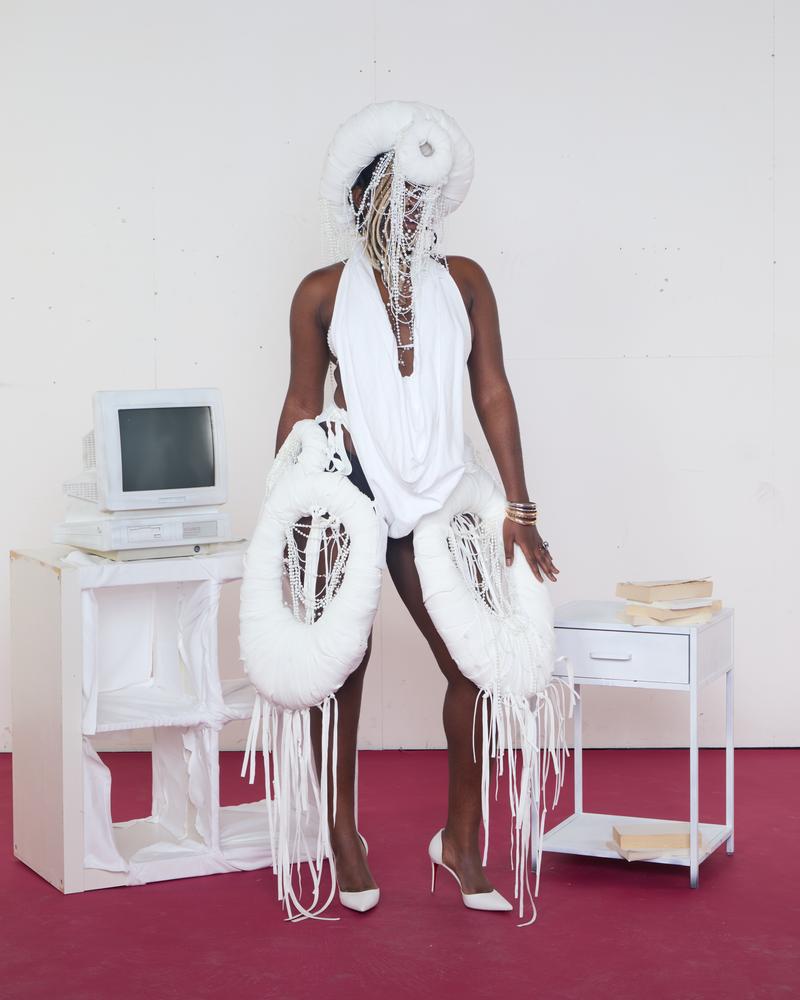

Thokoza Fisher (@tk_nikxfishr)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

TF: The starting point of my look came from looking at Sarah Baartman and how historically the female black body was something that was not seen as human and exhibited in derogatory ways and views. This led onto looking at how this is seen still in modern presence, with many black women being exoticized and fetishised in relationships, day to day and in the media.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

TF: By challenging dominant narratives around the gaze, fetishization, and power in representations of the Black female body, it keeps the ongoing conversations about decolonization, internalised racism, and bodily autonomy in fashion. The theory behind my look critiques how Black women, particularly in relation to other races, most notably white men, are still framed in power dynamics and fetishes.

I visualised this with heavy inspiration coming from Yoruba Orisha goddesses, these are figures which embody grace and sensuality coexisting with strength and power, using adornment, movement, and ceremonial references. Shifting the body from object to authority.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

TF: The strongest element of my look would definitely be the headpiece, which is heavily influenced by the Orisha Yemaya, where head coverings and ornamental pieces drive power and protection. By covering the face, the headpiece adds an element of mystery. In a context where covering the face is often associated with submission and vulnerability, it is reframed as an act of control and dominance, deciding what is seen and what is withheld.

If I had more time, I would love to push this idea further by expanding the scale and complexity of the head and hip pieces adding on more layered materials and movement-based elements, which would strengthen its presence both as a spiritual crown and a statement of authority and grace.

Tisya Khanna (@tisyakhxnna)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

TK: In terms of the inspiration for the look, I began with considering the colour white as my primary source of exploration. The piece considers white not as a colour, but as a liminal state — the interval between body and garment. Rooted in the poem Semiotic Theory by Kitasono Katue, my piece seeks to define garments as being structures in space, for the body to inhabit, positioning the real, yet undefined void as the central site of expression. Moreover, this is further articulated through a singular Fontana-like incision and a silhouette defined by geometry, stillness, and spatialism.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

TK: Building on this concept of defining white as an interval in space and time, due to its innate paradoxical nature, the look situates itself in the conversation of challenging the fundamental identity of clothing itself. Posing the question of whether a garment’s significance is found not its material presence, but in its absence and implied volume. The piece was approached on the basis of this very premise: one where expression can be achieved through subtraction, forcing the viewer to engage with the frame, the boundary, and the active void as the foundation elements of the design.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

TK: With regard to the aesthetic quality of the piece, I am particularly proud of the clean and precise construction of the piece. I often find that with more minimalist looks, when a single detail is off, it becomes very obvious, so creating a visually precise piece was very important to me. In terms of pushing the piece further, I am eager to explore the concept and apply it to different silhouette ideas. During the creation process, I experimented with numerous different folds and cuts, similar to origami, so would love the opportunity to take this to an even greater extent. In the future, I am also excited to work further on the glasses aspect and translate them further into an interesting pair of sunglasses.

Tyler Sastre (@tylersastre)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

TS: The starting point for this look was a male ballet dancer. His name was Vaslav Nijinsky, and he was part of the Ballet Russe. I used to do ballet so it really resonated with the imagery that follows. I researched a ballet he choreographed later in his career called “Afternoon of a Faun”. I looked at the idea of fauns, mythology, and hedonism to build a world attached to my Colombian heritage and use equestrian references.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

TS: As a contemporary, I don’t really like to reference anything happening in fashion. I find that it can be very derivative and the more you look at current works by others it floods your mind. I think in context the look stands in a space of sensuality, vulgarity, and sensitivity, which I like to use a lot in my work. I find that every project I approach I shy further away from outright sex and move towards a deeper understanding of what it means to show skin and why that is relevant in fashion, particularly in menswear.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

TS: I would say the strongest part of this look is the lace my grandmother made, combined with the ceramic shoulders. It really ties together the idea of heritage and craft that I started with in my research. If i had to push something further I would consider different broguing techniques and accessories like the shoes.

Claire Easton (@claireeastonline)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

CE: The starting point was thinking about the body as something both private and public, and examining the rituals and shame we inherit around that. I focused my research on Korean spas as intergenerational spaces of exposure and care, where the naked body becomes both highly visible and intensely normalized. From there, I focused on the gesture of a coat (a familiar form of protection) and what happens when that gesture becomes unresolved: held rather than worn, the promise of comfort without fully shielding the body. The project was trying to make sense of what we choose to show or to hide, to carry or to let go.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

CE: In terms of contemporary fashion discourse, I see the look less as a critique and more as a way of locating my own interests in it. I’m deeply influenced by designers and artists who have genuinely shifted paradigms, but I think it’s important to acknowledge that this work is part of an ongoing learning process rather than a definitive statement. I’m interested in how gesture and material behavior can carry meaning in quieter ways, and how restraint and misbehavior can shift familiar forms while leaving room for curiosity and play.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

CE: I think the strongest element is the gesture; particularly how the coat shifts from something worn to something that must be held. That misbehavior sets up the tension in the look, which is then reinforced by the contrast between the restraint of the front and the more exposed, crafted back. If I had more time, I would push that sense of misfit further, allowing the garment to feel even less settled on the body while maintaining clarity in the construction.

Estevan Bourquard (@estevanbourquard)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

CE: The starting point for this look is digestion. I looked at this process as a way of absorbing feelings. It was very natural to see it that way because every time I feel an emotion it’s in my body – and most of the time around my stomach. It really made me think about the relation between mind and body.

To continue the research, I then decided to look at the book The Complete Dictionary of Ailments and Diseases (Jacques Martel, 2012). I used this reference to develop the silhouette according to the interpretation of physical manifestations as expression of mental states – with an emphasis on body parts such as intestines and shoulder blades. In a nutshell, I wanted to show what’s hidden using the entrails as a way to show what’s happening inside our minds. I used a lot of medical references – the way we dissect human bodies, surgical sutures, organs, muscles – as well as the work of H.R. Giger who shows the uncomfortable in a very strong way.

It resulted in a garment that reveals its structure – visible boning, stuffing used as an ornament and felted wadding – and has a lot of openings – a total of 18 zippers are used to create the top, the jacket and the trousers.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

CE: This look positions itself as an alternative to traditional luxury by questioning both material value and garment construction – upcycled tablecloth, deadstock zippers and stuffing from upcycled toys. It’s important to change the perception of value : giving more value to meaning, process and technique more than rare and expensive fabrics. I am a true believer that the rarest silk fabric doesn’t necessarily produce the best garment.

By showing the structure of the garment – boning, wadding and stuffing – I reject the image of seamless and effortless fashion. I find structures beautiful and I want to share that beauty with others. The volume may echo to Met Gala looks but the meaning behind is quite the opposite.

Finally, showing the meat – I intentionally use this word as I am vegetarian – that builds our body is a way to make us reflect on our human nature. Most people tend to forget that we’re made just the same as all the other living beings.

Hopefully it might help to reconsider our relationship to other species: those we consume and those we eradicate for our comfort.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

CE: The strongest element of this look is the way it questions the construction of a garment by making its structure visible and by using materials that are usually not highlighted. Through this I try to rethink how an elevated silhouette can be built without relying on traditional luxury codes. This is something I always try to question in my work: how can I create a garment that challenges the industry standards.

If I had more time, I would push further the accessories, especially the footwear. I’m not the kind of designer who ends a project days before the show; I keep pushing until the last minute because I always feel there is something to improve. For instance, we had a critique of the project ten days before the show, and following that feedback I decided to create additional elements. During this process, I designed and made shoes for the first time and spent a lot of time working on them, but in the end they were barely visible on the runway. With more time, I would reconsider this balance and make the footwear more present and more integrated into the look, so it fully takes part in the overall construction and narrative of the garment.

Ayuna Kusano (@__marche7)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

AK: The inspiration for this project came from the film «KOKUHO» 2025.

When beginning this project, I started by researching how Japanese people interpret the concept of “artifacts.” In Japan, artifacts are not perceived merely as physical objects; intangible traditions, culture, and even communities themselves are also understood as artifacts. From this perspective, I developed the project with a focus on Japanese traditional performing arts and rituals such as Kabuki, sumo, and festivals. The core concept of my artistic practice is wabi-sabi. Wabi-sabi is a uniquely Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in simplicity, imperfection, and the passage of time. I focused on how beauty can be discovered within minimal forms, and how a striking accent can emerge from simplicity.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

AK: Sustainability is one of the most critical issues in the fashion industry today. I believe that the wabi-sabi sensibility—embracing aging, wear, and deterioration as something poetic rather than negative—can offer a partial solution to this problem. Expressing the beauty of simplicity and imperfection was the primary goal of this project. For me, wabi-sabi is most strongly felt when the passage of time and signs of aging are visible. This sense of time led me to the image of komorebi—sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees. Wanting to express movement that absorbs light and generates new reflections, similar to a sun catcher, I chose to work with resin.I combined this material with sagari, the ceremonial adornments worn by sumo wrestlers. Their seemingly random movement evokes the flickering quality of komorebi.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

AK: I believe the key appeal of this look lies in its ability to feel sacred and beautiful, while also carrying a subtle sense of mystery.

Daniela Paunero Boullosa (@danielapauneroboullosa)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

DP: My project titled “Contra Natura” began as an exploration into christianity and its criticism of what it deems sin and temptation. As someone who grew up in a christian culture, but never truly identified with its values, I wanted to rebel against its imposed sense of culpability and regret that fuels most christian beliefs. I looked into Nietszche proclamation that “God is Dead” and that we should not have to live a life of repent and submission in order to be deemed worthy. Diving into Christian sins I explored the imagery of apples, bitten, rotten, and into traditional nun’s attire such as the cornette hats, with candles serving as a central metaphor: light as divine guidance, and wax as society, slowly eroding and melting under the illumination.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

DP: Lately, I have found religion to be a very current topic amongst Gen Z, rising in popularity, mainly due to this constant search for something bigger than themselves, something to believe in beyond the chronically online society we are part of now. As interesting as I find this, I can’t help but look at everything through a feminist lens and unfortunately, religion is anything but. From establishing dress codes that cover and hide anything that may be a temptation to the male gaze, to making women feel guilty for having any kind of desire, for ruining their virtue. I wanted to address this and claim a sense of freedom for women to act on their instincts, embrace their urges and essentially sin without subjecting themselves to a life of repent. As far as we have come as a society, the standards when it comes to equality between genders regarding clothing, and connotations associated with more or less revealing clothes, still have a long way to go. And until then, I hope me and others in my generation will keep addressing the issue, me with fashion as my medium of expression and rebellion.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

DP: I believe the most striking aspect is the contrast between the large oversized cornette headdress with the delicate lace textile of the bodice. The large dimensions of the hat almost hiding the face of my model draws viewers in, in order to see the identity of who hides beneath such a vast structure. The peculiar origami construction of the headpiece also makes it stand out amongst others as it appears to be made of paper but clearly has the volume and weight of ultrasuede. Creating my own textile from the fabric through free embroidery on vanishing muslin makes my garment unique as well as taking into account new ways of creating fabric in a sustainable way, both by being able to use off cuts of table linen and also by building on the textile in the shape of the pattern pieces so that no waste is produced when cutting and sewing the bodice. The textile can also be adjusted and built upon to fit different models as more threads can be stitched without the need for redrafting pattern pieces.

If given more time I would have definitely liked to keep building on the lace textile by stitching and extending the threads along the seams to have a more exaggerated dripping effect that would link the bodice to the skirt. I would also have liked to keep exploring the sculptural pattern cutting technique of the skirt and maybe applied it to a different type of garment such as a jacket or a bag as an accessory for the look. Finally, extending the skirt with additional boning channels on the curved up flared section would have given the overall silhouette an even more striking quality but due to time restrictions I was not able to incorporate all of the under structure I needed.

Henry Moorhouse (@moorhousehenry)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

HM: The project started with looking at the context of Rebecca Horn’s Body Extensions, Isolated in a hospital Bed away from home. In this time both her parents passed away but yet she started to make these extensions of herself in the bed as a manifestation of her reaching out to people. They started the idea of community from isolation which I took into the design process.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

HM: My research for every project so far does not interact with past or recent shows or really the fashion world at all. I try to form an idea for an outcome that feels interesting or meaningful and then start thinking about how it may look on the body only in the design phase. I think this stems from my background in fine art and not having a fashion tutor before coming to Central Saint Martins this year, but ultimately makes the idea and research behind the outcome more cohesive and personal. As a Result of this I think there is a place for my look in contemporary fashion, but not one that tries to critique.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

HM: The construction of the trousers being individual feathers cut by hand. This was done so they would all be unique as if they each had fallen of different birds and pieced together in a sort of community. I believe it to be the strongest aspect because it created a trouser that is put on traditionally and tried around the waist, but isn’t visually consistent with a trouser.

Julia Miranda (@juliavee_miranda)

AR: What was the starting point for this look?

JM: My Reset project looks into temporary structures and natural materials. Exploring both their protective qualities and fragility. Through a creative design process, I combined my research and development to create shape proposals. Starting with textiles and placing them on a miniature mannequin, which allowed me to transition into larger scale ideas. Resulting in a wearable outcome that is structured, yet decaying over time.

AR: How does the look position itself within contemporary fashion discourse, and does it offer a meaningful critique or expansion of existing paradigms?

JM: Focusing on natural materials impermanence, holds a place in today’s current discourse on sustainable and ethical fashion. Highlighting the strength that these materials can have, while also showcasing their decomposition leads to a more circular fashion space.

AR: What do you think is the strongest element of this look—and what would you push further if you had more time?

JM: The frayed textures that drape around my garment and structure I feel highlights my concept of impermanence well. Although my outcome is complete, as a result of my creative process, I would further explore how I can push shape and form. Experimenting with various scales, and how that impacts a garments movement and wearability.