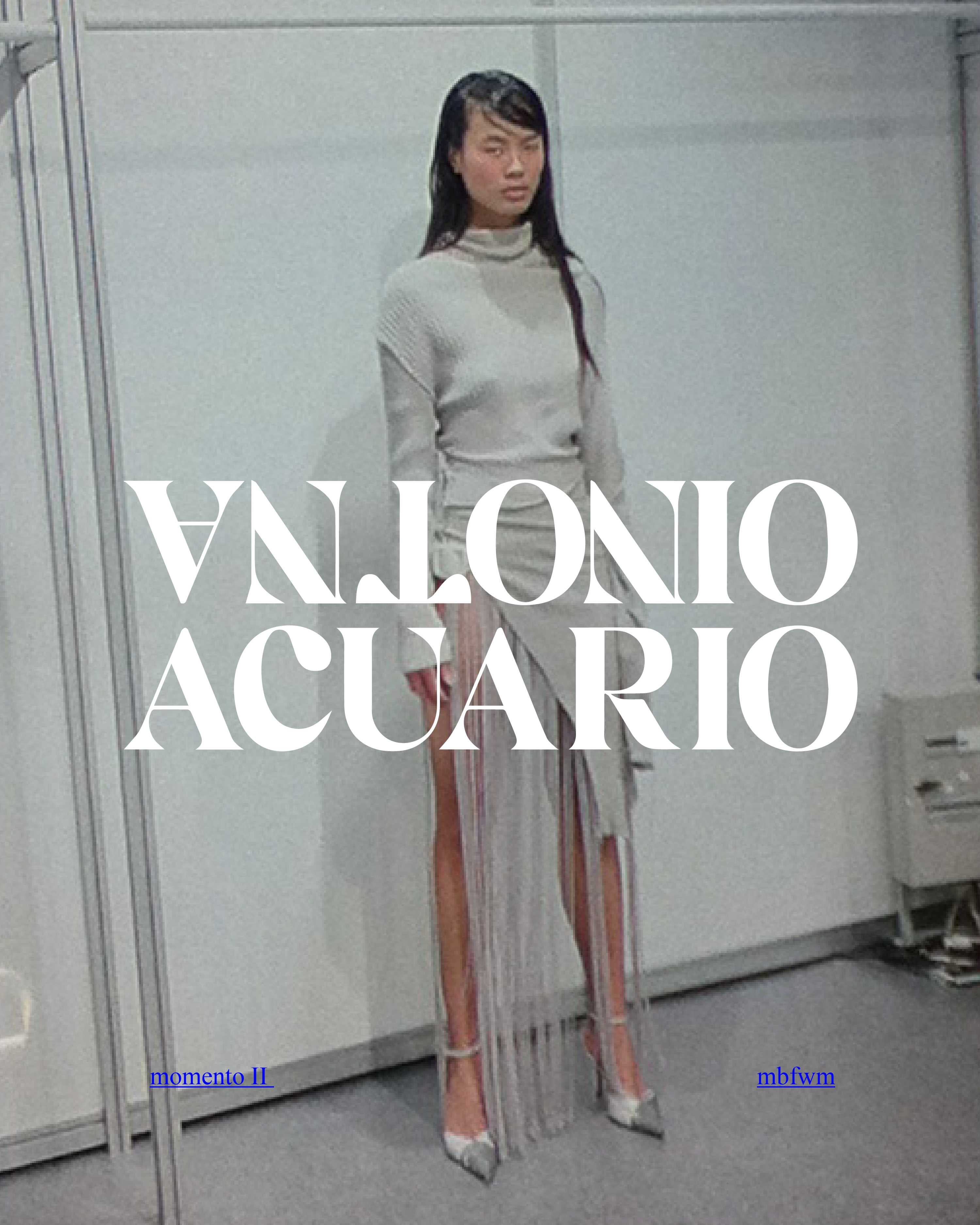

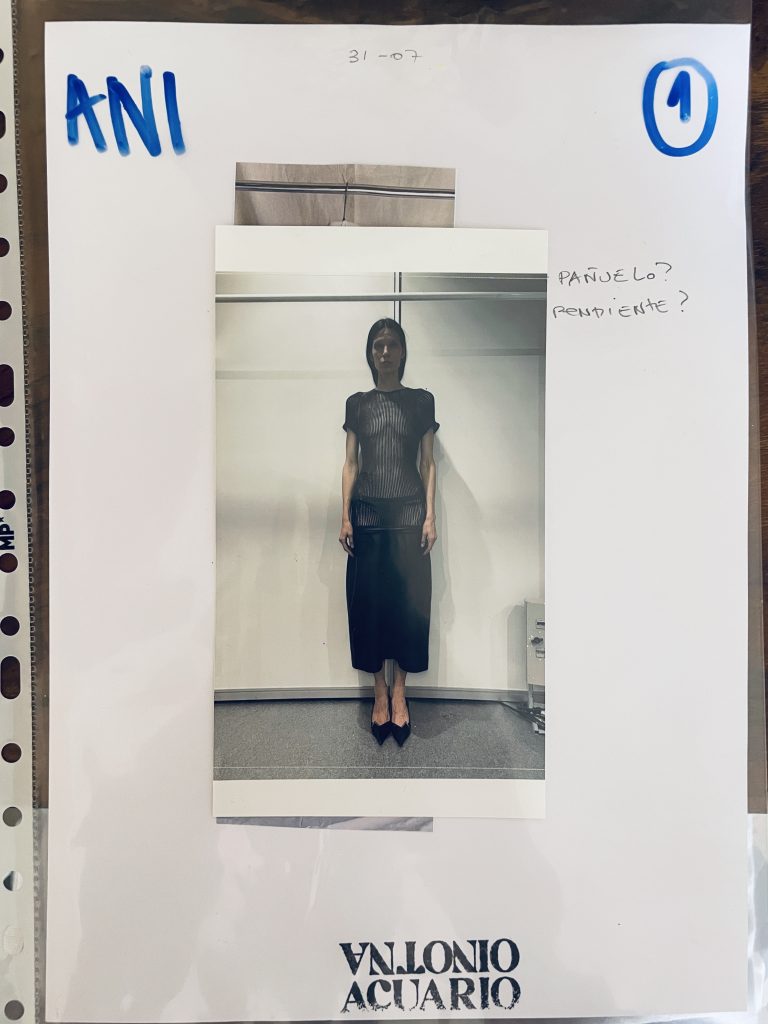

ANTONIO ACUARIO BY ANTONIO CONTRERAS: AN IN-DEPTH INTERVIEW

In this interview, Chilean designer Antonio Contreras, founder of the Antonio Acuario brand, reflects on the current role of the designer, their relationship with clothing, and the importance of working with honesty and creative independence. From his Barcelona studio, Contreras shares his vision on sustainability, upcycling, and the need to rethink the industry’s rhythms. Through his work, he proposes a more conscious and emotional approach to creation, where each garment engages with memory, identity, and time.

Gadea Delgado: Antonio, how do you define the role of the designer today if it’s no longer necessarily tied to knowing how to sew, draw, or produce as it once was?

Antonio Contreras: I think the role of the designer today is more like that of an editor or an interpreter than a pure artisan. It’s no longer just about manufacturing, but about reading clothing and its context, understanding how it moves, where it comes from, and where it can go. In my case, knowing how to sew gives me independence, but I don’t think it’s an obligation: the important thing is to have something to say with a garment and to know how to build your own language with it.

GD: You’ve said that you’re not interested in fashion, but in clothes. How do you think that difference has shaped your career and your creative process?

AC: Fashion is about time, trends, and speed. Clothes, on the other hand, speak of people. I relate to clothes as I do to a body, to its memories, its wrinkles, its smell. I’m not interested in producing «novelty,» but meaning. That’s why many of my pieces are born from other pieces I’ve already experienced… I like to think that I don’t create them, but rather continue them.

GD: Do you feel that the industry is beginning to open up to designers who, like you, reject calendars, seasons, and commercial rigidity?

AC: Yes, but still with nuances. There’s an aesthetic openness, but not necessarily a structural one. Brands may applaud the discourse of change, even if they continue to operate with the same consumer logic. I prefer to remain on a quieter side, where the garment sets the pace, not the market.

GD: What would you say to someone who still sees independent fashion as a stepping stone before «making it» to the mainstream industry?

AC: I would tell them they’re looking at it with the wrong eyes. Independence isn’t a waiting room; it’s your own territory. It’s where you can make mistakes without anyone asking for explanations, where you can spend months on a single garment if that’s what it needs. I’m not waiting to «make it» anywhere. Right now, I’m where I want to be, flowing with the flow, seeing what opportunities arise for Antonio Acuario that resonate with the brand’s message. The mainstream industry has its own rules, and that’s fine (or not), but they’re not mine. I prefer the freedom of not having to justify why a collection has five pieces or why I don’t offer discounts. That, for me, is what it means to make it.

GD: In this return with Antonio Acuario, how do you negotiate nostalgia with the need to avoid repeating yourself?

AC: I don’t know if you negotiate; I think you coexist with them. Nostalgia is there, like a murmur, but I don’t let it paralyze me. Sometimes I pick up a garment that reminds me of something from my childhood or a specific place, but I don’t copy it, I alter it. It’s like returning to a place you knew but with fresh eyes. Memory gives me material, but curiosity tells me what to do with it. And if I feel I’m repeating myself, I simply stop. I prefer silence to redundancy. That said, I also believe that repetition isn’t bad, since it can be another kind of exercise to achieve something.

GD: Do you feel that being Chilean has influenced your perspective on clothing and design in any particular way?

AC: Absolutely. There’s an expression in Chile: “pie forzado.” This is an obligation or rule that marks the starting point of any task or thing you have to do. In my case, the “pie forzado” was my beginnings: not finding raw materials in Chile that met my expectations led me to search for other resources, such as dead stock, secondhand garments, or fabrics not originally intended for clothing. There’s also a certain melancholy in Chilean culture, a way of looking at the past that isn’t just nostalgia, but respect. I think that seeps into how I work… I don’t throw things away, I don’t discard them, I don’t forget. Everything has a second chance, and that comes from deep within.

GD: When does a used garment convey enough to you to deserve a second life in your world?

AC: When I look at it and feel something. It could be a hand-sewn stitch, a stain that tells a story, a cut that’s no longer in style. Sometimes it’s the texture or the fabric, other times it’s simply an intuition. It’s not something I can explain logically; it’s more visceral. There are garments that call to me and others that simply don’t. And when one calls to me, I know I have to listen to it, understand it, or put it away until I see it and say, «Now I see you.»

GD: Is there any fabric or type of garment that, no matter how often it appears before you, you always reject?

AC: Yes, and it frustrates me a lot, since they’re generally garments that were born dead, flawed in quality from the very beginning of production. Fast fashion has generated so many wasteful, disposable, discardable garments, made for landfills. We have to keep this in mind when we consume, since the responsibility lies with everyone, not only with fast fashion brands, but also with us who consume them and make this a business for these companies.

GD: In your search for materials, have you found pieces with personal stories that you decided to keep as they were?

AC: No. If I find something from my archives that I want to keep as is, I buy it, but I don’t use it for Antonio Acuario; I keep it in my closet. Giving a second life to garments with personal history, for me, is what gives meaning to the most important pieces. I have a couple of things I made with garments that a friend donated to me; these belonged to her mother, and for me, working with them was an honor.

GD: Do you think that sustainable fashion, as it’s understood today, is becoming more of a label than a real paradigm shift?

AC: Yes, and that worries me. I also think it’s good that it’s being talked about more and brought to the forefront, because you have to start somewhere. Now, sustainability is being sold as just another product, as if it were an adjective you can slap on a label and that’s it. But real sustainability is uncomfortable, slow, and expensive. It’s about working with what you have, not what you want. In other words, we shouldn’t produce more just because we can. And that doesn’t sell as well as an «eco-friendly» bag made in a factory that continues to exploit workers. For me, sustainability isn’t a marketing strategy; it’s a way of living and working. I hope that in the future we’ll reach a point where it’s not even an issue, where things are done right, the way they should be.

GD: How do you imagine upcycling will evolve in the next ten years? Do you see limits or infinite possibilities?

AC: I think it’s going to explode (I hope so), but also that there’s going to be a lot of noise. Everyone will want to do upcycling (it’s already happening) because it’s trendy, but few will truly understand what it means. The limit isn’t in the technique or the materials, it’s in honesty. Are you upcycling because you believe in it or because it sells? That’s the question. I see countless possibilities and I hope the future surprises us with many more, but for this to happen, we all have to work on it.

GD: What’s a typical workday like in your Barcelona workshop? Is there a routine or is it all controlled chaos?

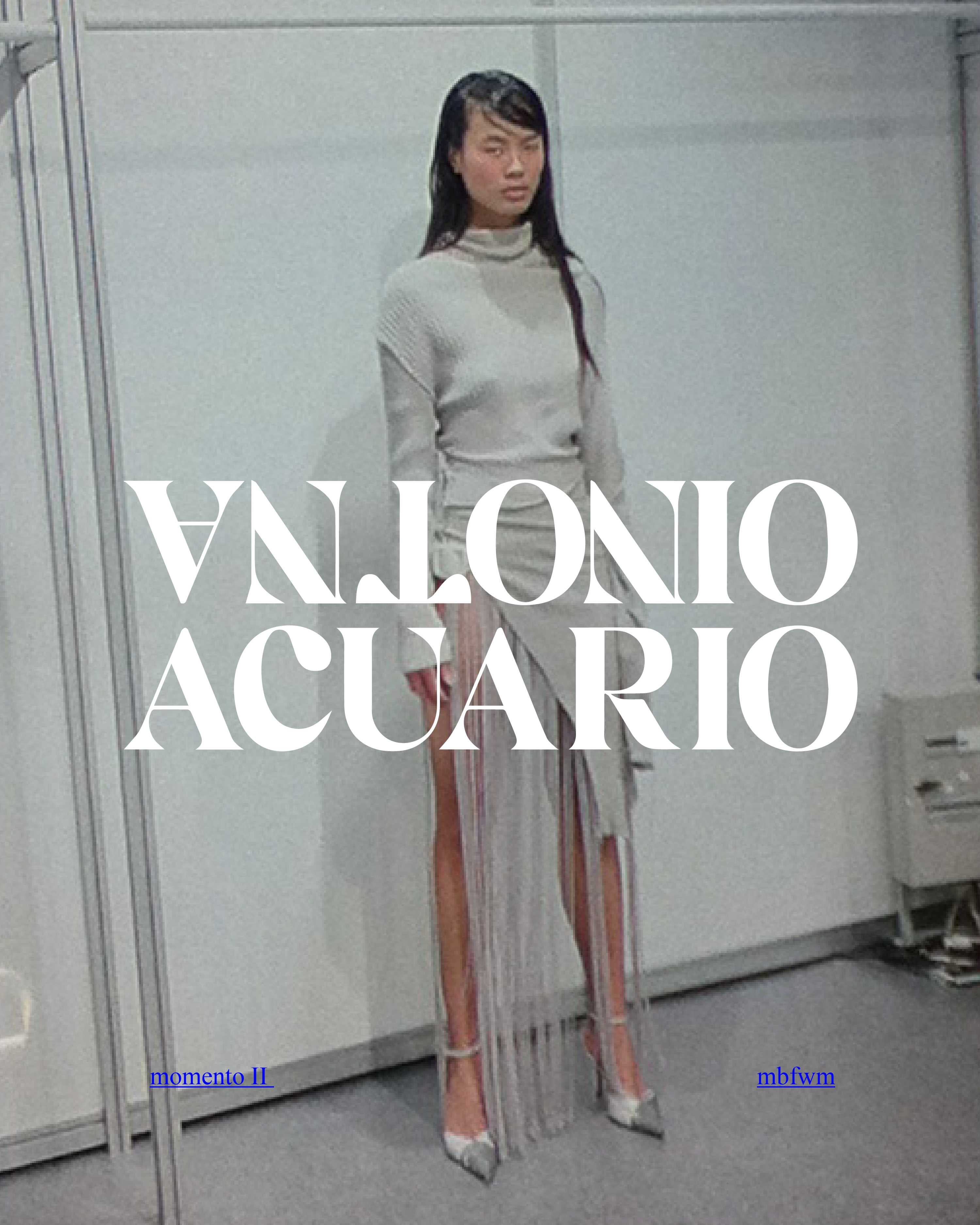

AC: My day-to-day is quite hybrid. I spend many hours in the workshop, working directly with the pieces, testing volumes on the mannequin, and sculpting my silhouettes until they’re just right. There are also days of research, of searching for materials on location, of finding inspiration by discovering garments in markets, vintage shops, or secondhand stores. And then there’s the creative direction aspect, which involves thinking about how the entire project is communicated: from the lookbook to the runway show or the digital experience. It’s a back-and-forth between analog and digital, always keeping in mind that it has to generate the least possible environmental impact, so nothing is printed or used that would have to be thrown away later.

GD: Has a garment ever ended up being something completely opposite to what you initially envisioned? Do you let yourself be surprised by the process?

AC: Always! I might have an idea of how the garments or cuts work on the mannequin, but only as I’m sculpting directly on it do I know what the final result will be. I think I have to be willing to flow with the process, to keep going, even if it takes me to places I didn’t plan.

GD: What role do your emotions or mood play in the decisions you make about a garment in progress?

AC: Quite a bit. There are days when I think I shouldn’t touch anything, but other times that emotion is exactly what the garment or I need. It’s as if each piece carries a piece of my mood sewn inside.

GD: Have you ever felt creatively blocked while working on the mannequin? How do you deal with those moments?

AC: Yes, and I think it’s normal. When that happens, the best thing I can do is step away and do something else. I go out and find materials to work with, I organize, or I read. Sometimes the block comes from being too close, from forcing something that doesn’t want to come out. Other times I simply need time. Creativity isn’t a tap you can turn on whenever you want; it has its own rhythm. And I’ve learned to respect it and manage it, even though it’s difficult.

GD: Is there a piece you’ve remade so many times that you feel it’s no longer yours?

AC: No.

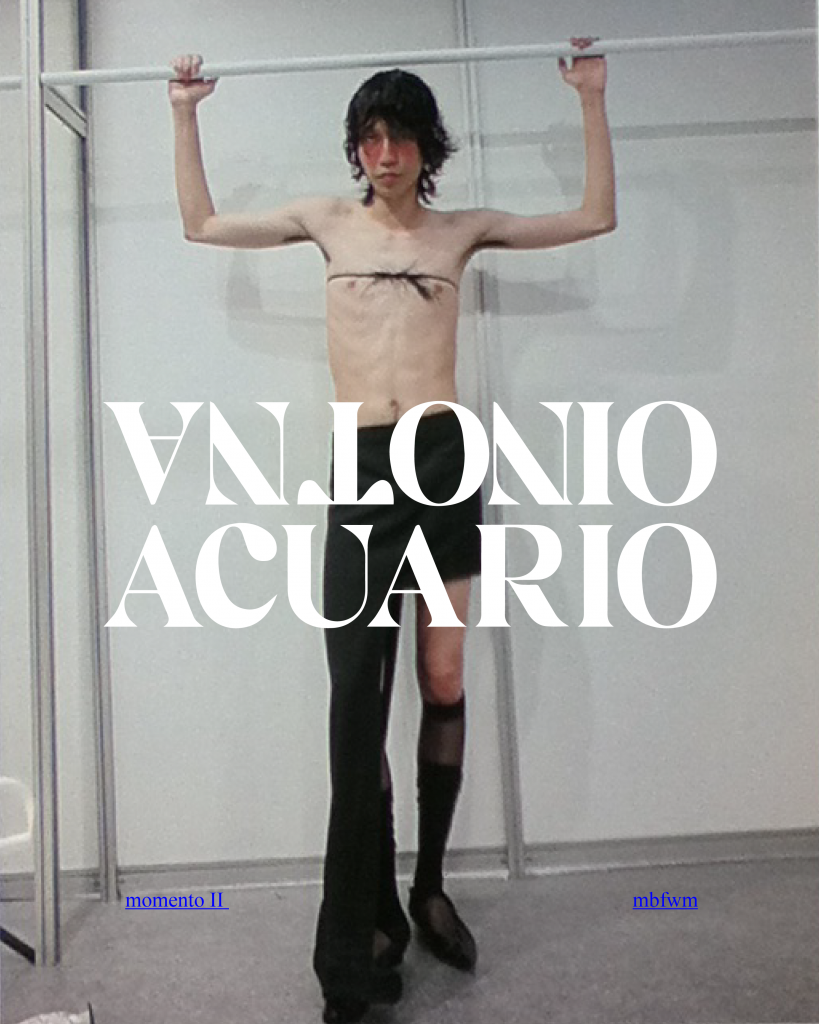

GD: In «Moment II,» you talk about childhood memories and feminine gestures that you didn’t allow yourself to inhabit before. How was it emotionally to confront that part of your history?

AC: Opening that drawer to create this collection was beautiful and also liberating. In the end, it became a reconciliation with that part of me that I had silenced and is now flowing.

GD: What silences or absences did you want to break with this collection?

AC: Things you couldn’t do because they «weren’t for boys.» I wanted to break the silence surrounding everything I was told I couldn’t be. And I also wanted to give a voice to the women in my family: to my mother, to her hands, to her support. This collection is a little bit for her, a little bit for the boy I was, and a little bit for the man I am now.

GD: How do the two opposing forces of the collection, «complexity and minimalism,» interact within your own body and experience?

AC: I believe in change, in changing my mind and ideas when something no longer makes sense. It’s a constant and sometimes contradictory dialogue, but it’s part of the intelligence of growing and moving forward. There are days when I need silence, cleanliness, an empty space; and there are days when I need noise, layers, chaos. I think those two forces coexist within me all the time: the need to say a lot and the need to be silent. The complexity comes from my history, from everything I’ve lived through and kept inside. The minimalism comes from the need to breathe, to not drown in the noise. And clothing is where those two forces meet: distancing myself from the world and belonging to it.

GD: Were there any looks from «Momento II» that were emotionally difficult for you to finish because of what they represented?

AC: There are pieces I started more than three years ago that only saw the light of day for this collection, but that’s because they’ve now found the expression I was looking for to make them special. Not because of what they represented, but because they weren’t ready before, and now they are, for me.

GD: What was it like presenting such an intimate collection on a platform as high-profile as MBFW EGO?

AC: The collection isn’t intimate; what’s intimate is my approach to finding inspiration and the perspective from which I project my work. Presenting it at MBFW is a great opportunity to gain more exposure and for Antonio Acuario’s message to reach a wider audience.

GD: What do you still retain from the Antonio Contreras who founded «A de Antonio,» and what have you completely left behind?

AC: I still have the sensitivity, the way I look at clothing, and the respect for the body and history. I haven’t lost that. But I’ve left behind the anxiety, the need to fit in, to be validated by the industry. I’ve left behind the fear of going slowly, of not producing enough, of not being «relevant.» Now I work at my own pace, and that’s something I wouldn’t trade for anything. «A de Antonio» was a laboratory where I explored my initial ideas, which lasted until 2016. Afterward, due to various factors, I felt the need to stop, observe, and rethink my path. With “Antonio Acuario,” I return with a freer, more mature perspective and a much clearer commitment to the environment, working by hand with pieces that are currently unique. The name change reflects this evolution and also a more intimate identity, directly connected to myself and my universe, bringing to light all those gestures and silhouettes that, in the distant past, I felt I couldn’t make my own. This is ultimately reflected in freer pieces, born of chance and memory, that flirt with all the things I saw as impossible for me, due to a heteronormative structure with which I no longer identify.

GD: Do you feel that Antonio Acuario is an alter ego, a mask, or your most authentic self?

AC: It’s not a mask or a character. It’s a way of expressing what I do, of giving it a space without having to explain myself. Antonio Acuario is a place to experiment in the present with respect to my past, looking toward my future. It’s a part of me, not my whole self.

GD: Finally, if you could imagine your clothes talking, what message do you think they would convey?

AC: Freedom.

Questions by @gadeadelgadoo

Translated by @alraco43